Japanese mythology blends Shintō and Buddhist traditions, tracing cosmic beginnings, natural forces, and the stewardship of the land to a vast network of kami—deities who govern everything from the sun and storms to learning and prosperity. Stories preserved in the ‘Kojiki’ and ‘Nihon Shoki’ describe how the islands were formed, how rulers traced their lineage to the heavens, and how rituals and festivals maintain harmony between people and the divine. Many of these gods still anchor Japan’s spiritual life through grand shrines, matsuri, and everyday offerings.

This lis highlights central figures known for creation, sovereignty, nation-building, war, the sea, the moon and sun, and the lifelines of rice and fire. You’ll find where they’re worshipped, the myths that define them, and symbols—like sacred mirrors, swords, fox messengers, and thunder drums—that make their presence recognizable across Japan.

15. Sarutahiko Ōkami

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsSarutahiko Ōkami is the towering guide of crossroads and journeys who meets Ninigi-no-Mikoto as he descends from heaven, clearing the way for the heavenly lineage to take root on earth. He is associated with strength, guidance, safe travel, and beginnings—roles reflected in his domain over paths, bridges, and thresholds. He is often depicted with a long nose and imposing stature, signaling a guardian presence that stands at the liminal point between realms.

Major devotion centers include Tsubaki Grand Shrine (Tsubaki Ōkami Yashiro) in Mie Prefecture, where rites for guidance, purification, and successful endeavors are conducted. Martial traditions sometimes invoke Sarutahiko as a patron of discipline and correct form, aligning his guidance with harmony of movement and intent during training and performance.

14. Tenjin (Sugawara no Michizane)

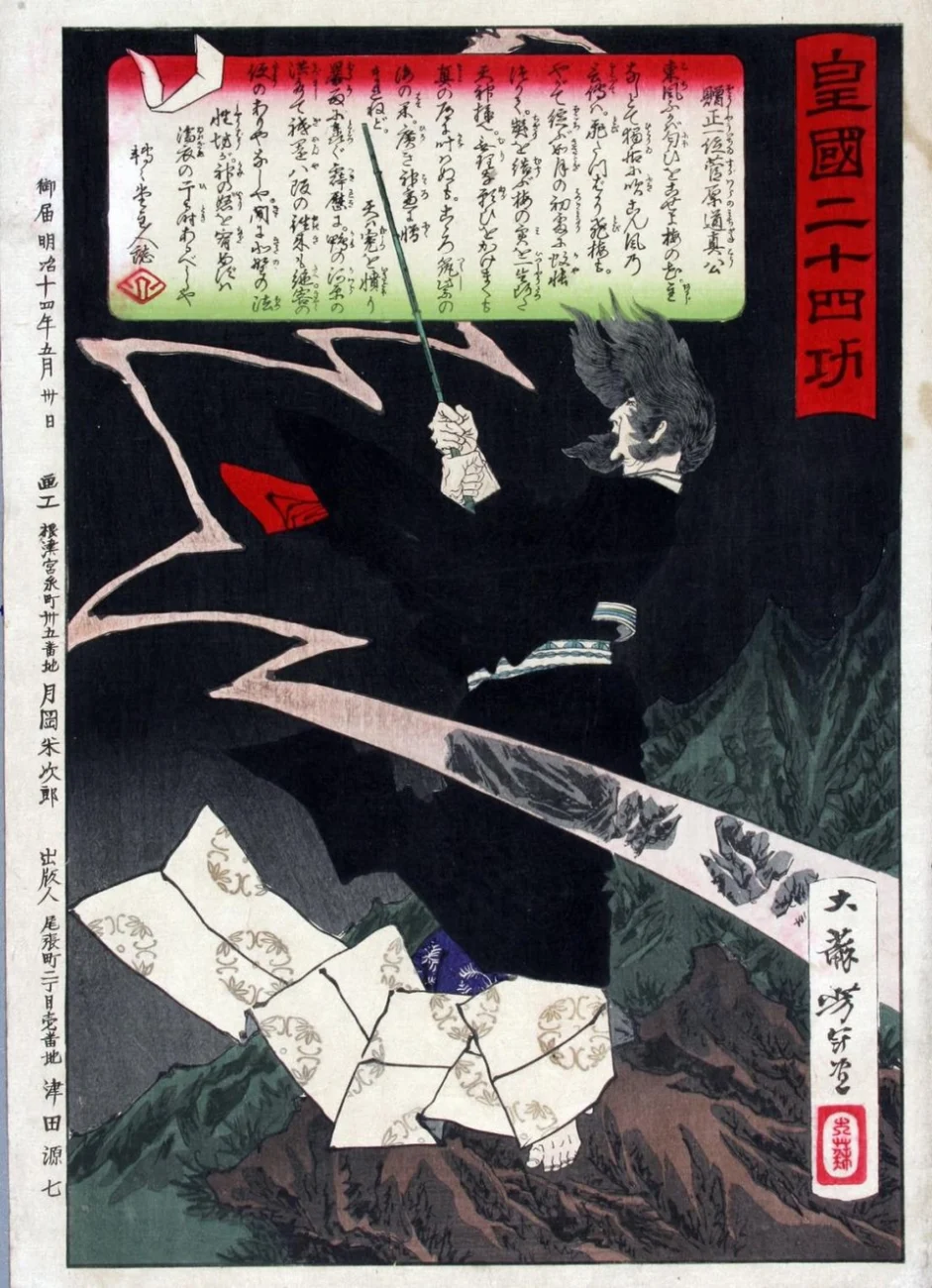

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Tsukioka YoshitoshiTenjin is the deified form of Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), a renowned Heian scholar and statesman whose learning and poetic skill made him an enduring symbol of scholarship. After his untimely exile and death, calamities in the capital led to his appeasement and deification, transforming him into the powerful patron of students, literature, and calligraphy.

Kitano Tenmangū in Kyoto and Dazaifu Tenmangū in Fukuoka are foremost among thousands of Tenjin shrines. Students visit to offer ema (votive plaques), pray for exam success, and honor the plum blossoms—flowers closely linked to Michizane. His ox symbolism appears in statuary and amulets, where touching the head is believed to confer wisdom.

13. Fūjin

Tawaraya Sōtatsu

Tawaraya SōtatsuFujin, the wind kami, is instantly recognizable carrying a great sack from which the winds blow. In art he appears as a wild, muscular figure racing across the sky, a counterpart to the thunder god Raijin. Together, their interplay explains seasonal storms, typhoons, and the patterns that shape agriculture and seafaring.

Representations of Fujin in temple and shrine precincts emphasize the importance of favorable winds for travel and crops. Historical screens and sculptures depict him alongside Raijin, teaching cosmology through imagery: wind that clears the air, drives clouds, and powers storms, and a force that communities propitiate with offerings in hopes of gentle weather and protection from destructive gales.

12. Raijin

Katsushika Hokusai

Katsushika HokusaiRaijin governs thunder and lightning, often shown beating a ring of taiko-like drums marked with tomoe symbols. His presence signals raw atmospheric power—cloud-rending thunderclaps, flashes that fertilize the earth, and storms that demand ritual attention. In iconography he appears with wild hair and a fierce aspect, inseparable from the drama of summer squalls.

Raijin’s imagery pervades shrines and temples, where rituals seek both protection from lightning and blessings for harvests. He frequently appears paired with Fujin in statuary and painted screens, a duo that encodes the relationship of wind and thunder. Farmers historically interpreted thunder as heralding rains essential for rice, making Raijin’s goodwill a practical concern.

11. Kagutsuchi (Hi-no-Kagutsuchi)

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsKagutsuchi is the fire deity whose birth fatally burns Izanami, setting in motion the mythic descent to Yomi and the cycle of death and purification. In response, Izanagi slays Kagutsuchi, and from the god’s remains arise mountains and further kami—an episode that links destructive blaze to the generative power of molten earth and volcanic terrain.

Kagutsuchi’s dual nature—destructive fire and necessary hearth—underlies fire-prevention rites and festivals. Shrines dedicated to him and related fire deities sponsor ceremonies for safe foundry work, smithing, and household protection. Fire brigades and communities have long observed appeasement rituals, acknowledging both hazard and the indispensable role of controlled flame in daily life.

10. Hachiman

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsHachiman is the widely venerated deity of archery and war, protector of communities and states. Emerging through Shintō-Buddhist syncretism as Hachiman Daibosatsu, he was honored as guardian of Tōdai-ji and the Great Buddha in Nara, reflecting his role as a protector of the realm and Buddhism alike. His cult expanded alongside warrior rule, linking military virtue with divine sanction.

Usa Jingū in Ōita Prefecture is the head shrine of Hachiman worship, with countless branch shrines nationwide. Emblems such as the dove and bow express his patronage of martial discipline and communal order. Villages and clans long sought Hachiman’s favor before campaigns and in times of unrest, and he remains central to festivals celebrating protection and resilience.

9. Takemikazuchi

Yashima Gakutei

Yashima GakuteiTakemikazuchi is a formidable war and thunder deity closely associated with the sacred sword and martial authority. In myth he descends to pacify the land, compelling submission so that the heavenly descendant can rule. Accounts emphasize his prowess and role in legitimizing transfer of rule from the earthly to the heavenly line.

Kashima Jingū in Ibaraki Prefecture enshrines Takemikazuchi, famed for the “kaname-ishi” keystone said to pin down the earth-shaking catfish (namazu) that causes earthquakes. Sword traditions, sumō origins lore, and martial rites connect to his worship, highlighting discipline, rightful authority, and the containment of disruptive forces.

8. Ryūjin (Watatsumi)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Utagawa KuniyoshiRyūjin, the dragon sea god, rules the ocean’s depths from the palace Ryūgū-jō and appears in legends holding tide-controlling jewels. Maritime clans revered him for safe voyages, bountiful catches, and the mastery of tides and currents that defined coastal life. Myths recount exchanges of treasures and time between his realm and the human world.

Shrines along coasts and islands honor Ryūjin or related sea deities under the name Watatsumi. Sailors historically sought his favor before departures and gave thanks after landfall. Stories of the tide jewels, which grant ebb and flow, encode understandings of lunar cycles and tidal timing vital for navigation and shellfish harvesting.

7. Ōkuninushi (Ōnamuchi)

Yashima Gakutei

Yashima GakuteiŌkuninushi is the great nation-builder who organizes the land, heals, and mediates relationships. Tales recount his aid to the White Hare of Inaba and his mastery of medicine and magic. After developing the land, he cedes rule to the heavenly line, continuing as a guardian of the unseen world and human bonds.

Izumo Taisha in Shimane Prefecture is his principal shrine and a center for en-musubi (relationships and matchmaking). Ritual calendars there gather kami from across Japan during the tenth lunar month (Kamiarizuki in Izumo), reflecting his authority in convening deities. Offerings emphasize prosperity, health, and harmonious connections among people and communities.

6. Inari Ōkami

Ogata Gekkō

Ogata GekkōInari Ōkami presides over rice, fertility, and prosperity, domains that historically determined survival and, in modern times, business success. Foxes (kitsune) serve as messengers; keys, sheaves of rice, and jewel-like magatama often accompany their statues at shrine gates. Inari worship adapts readily, linking agriculture with commerce and household well-being.

Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto is the head shrine, famous for avenues of vermilion torii donated by patrons in thanks for favors granted. Countless branch shrines make Inari one of Japan’s most widespread deities. Seasonal offerings mark planting and harvest, while merchants and artisans petition for thriving trade, craftsmanship, and protection of storerooms.

5. Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsTsukuyomi governs the moon, whose phases regulate tides, calendars, and agricultural cycles. Classical chronicles describe him as sibling to the sun goddess Amaterasu and the storm lord Susanoo, born from Izanagi’s purification. A famous episode tells of Tsukuyomi slaying the food goddess Uke Mochi, leading to estrangement from the sun and the separation of day and night.

Tsukuyomi’s worship appears in select shrine precincts, including Tsukiyomi-no-Miya at the Ise complex. His lunar authority underpins timing for rituals, fishing, and farming, making the moon’s cycles a practical framework for scheduling community life. Symbolism links him with clarity, order, and the quiet governance of night.

4. Susanoo-no-Mikoto

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Utagawa KuniyoshiSusanoo embodies storms and sea squalls, a force that disrupts yet also protects when properly honored. Exiled from heaven for unruly deeds, he proves his valor by slaying the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi, from whose tail he draws the sword later known as Kusanagi—one of the Three Sacred Treasures. His deeds connect tempestuous power with guardianship and heroic rescue.

Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto and other major shrines enshrine Susanoo, where summer festivals invoke protection from epidemics and disaster. Maritime communities historically addressed him as a sea protector, while his serpent-slaying feat links him to the defeat of chaos and the bestowal of regalia that signify legitimate rule.

3. Izanami-no-Mikoto

Kobayashi Eitaku

Kobayashi EitakuIzanami, alongside Izanagi, performs the first creation of the Japanese islands (kuniumi) and the birth of myriad kami (kamiumi). Her death in childbirth and subsequent presence in Yomi establish the boundary between life and death, and the need for purification after contact with death’s realm. Tales of her pursuit underscore the irrevocable divide that mortality imposes.

Shrines honoring Izanami emphasize fertility, safe childbirth, and remembrance. Rituals derived from her story include purification practices that follow contact with death and blood, structuring community responses to loss and renewal. Landscapes associated with her—volcanic fires, chthonic spaces—anchor myths to features of the archipelago.

2. Izanagi-no-Mikoto

Kobayashi Eitaku

Kobayashi EitakuIzanagi, with Izanami, gives shape to the archipelago and begets key deities. After his flight from Yomi, he performs misogi (ritual bathing) whose purity brings forth Amaterasu from his left eye, Tsukuyomi from his right, and Susanoo from his nose—an origin that links purification to cosmic order. His actions establish foundational rites of cleansing and separation from impurity.

Izanagi Jingū on Awaji Island commemorates his role in creation and ritual precedent. Shintō purification—whether at a shrine’s temizuya basin or through larger rites—traces back to his misogi, aligning social and spiritual cleanliness with the maintenance of harmony. His begetting of the principal sky deities frames the divine genealogy that underlies sovereignty.

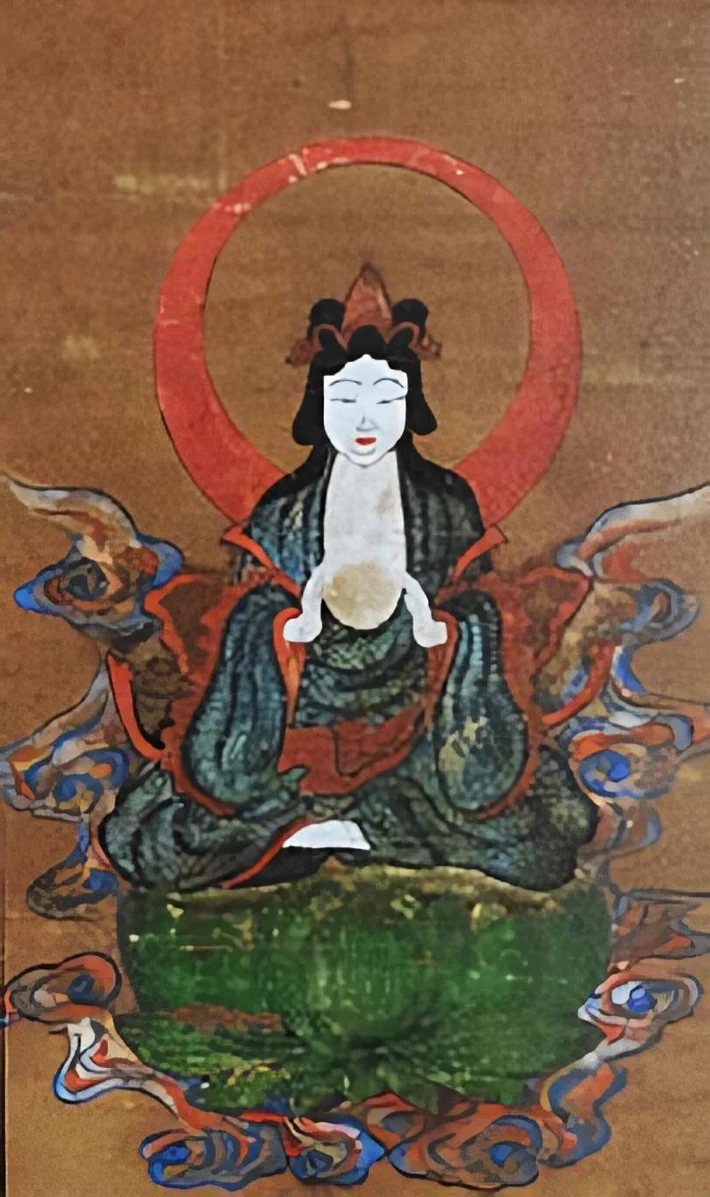

1. Amaterasu Ōmikami

Kunisada

KunisadaAmaterasu is the sun goddess whose light governs life, timekeeping, and agriculture. When she withdraws into the Rock Cave of Heaven (Ama-no-Iwato) after conflict, darkness covers the world until the other kami lure her out with ritual, dance, and the sacred mirror—events that establish the power of ceremony to restore balance. She is ancestress of the imperial line through Ninigi-no-Mikoto.

The Grand Shrine of Ise (Ise Jingū) is her supreme shrine, where the sacred mirror Yata-no-Kagami symbolizes her presence. Periodic shrine rebuilding (Shikinen Sengū) renews the structures and crafts on a regular cycle, reflecting principles of purity, continuity, and transmission. Festivals and state rites invoke her blessing on the nation’s well-being and harvests.

Share your thoughts below on which deities you’d place at the top and why in the comments.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·