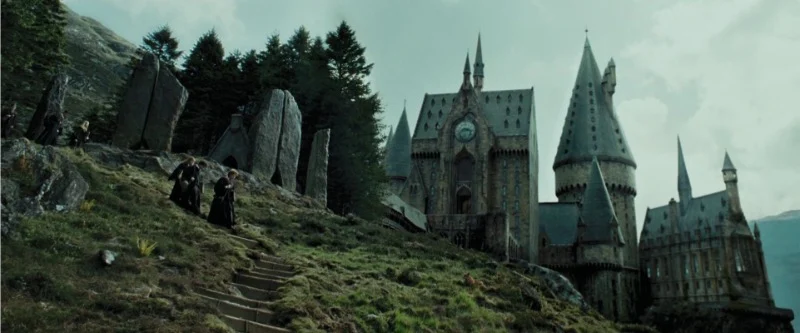

There is a reason so many fans remember the third film for its moodier look and confident storytelling. ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’ marked a shift in style and craft that touched everything from costume choices to camera movement to how the grounds of Hogwarts were imagined on screen. The production leaned into practical builds, unusual locations, and a fresh visual language that set it apart from what came before.

Behind that new feel sat hundreds of specific decisions that shaped what you see in every frame. From a triple decker bus that really drove through London traffic to a map that existed as a working prop with intricate folds, the crew built and tested ideas that would become signatures of the film. Here are ten pieces of production history and behind the scenes detail that explain how this chapter came together.

Alfonso Cuarón’s first time steering the wizarding world

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’ was directed by Alfonso Cuarón, who joined the series after two entries by Chris Columbus. Cuarón worked closely with department heads to push a more naturalistic approach to sets, lighting, and costumes, encouraging the cast to wear casual layers and school uniforms in looser ways that reflected daily student life.

He also asked the main trio to prepare in character essays to deepen their understanding of Harry, Hermione, and Ron. Emma Watson delivered an extensive paper as Hermione, Daniel Radcliffe wrote a concise response as Harry, and Rupert Grint famously did not turn one in like Ron, which the production used as a small insight into how the characters might behave.

Hogwarts moved and expanded for a new layout

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The production rethought the placement of key Hogwarts locations for ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’. Hagrid’s hut was rebuilt in Glen Coe in the Scottish Highlands, which allowed wide shots of the surrounding valley and brought more dramatic geography into outdoor scenes.

Other grounds features shifted to accommodate the new locations and camera plans. Paths, bridges, and courtyards were redressed or repositioned, and additional exterior sets were constructed so that scenes could play from interiors out to the hills without breaking visual continuity.

Michael Gambon’s first appearance as Albus Dumbledore

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.This film introduced Michael Gambon in the role of Albus Dumbledore after the passing of Richard Harris. The costume team updated the headmaster’s wardrobe with textured fabrics and a slightly less formal silhouette that fit the film’s more lived in atmosphere.

Gambon’s arrival also meant adjustments in staging and blocking so that the new performance could be captured from angles that suited both the actor and the sets. Dialogue scenes were restaged on existing builds and new coverage was shot to match the previous films where continuity required it.

The Knight Bus was a real vehicle that hit real streets

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The Knight Bus you see weaving through London was built from stacked bus bodies mounted on a custom chassis. It did drive for exterior shots, with additional sequences completed on controlled stretches of road and on a stage where backgrounds were added later.

To sell the impossible speed, the crew used undercranked cameras and carefully timed passes through traffic. Interior scenes were filmed on a gimbal set that allowed the beds and passengers to jolt on cue while outside plates were projected or composited to match the motion.

Dementors came to life with puppetry and digital work

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.Dementors began as elaborate puppets suspended on set so the windblown, cloth like movement could be captured in camera. The crew filmed these passes and then layered digital elements on top, replacing sections with visual effects while keeping the physical performance as a guide.

Close shots added facial distortion and vapor trails that interact with breath and cold air. For the lake sequence, multiple plates were combined with atmospheric effects to create the sense of temperature drop, and the sound team built a spiraling audio design that ramps as the creatures approach.

Buckbeak blended full scale animatronics and computer graphics

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.A full size Buckbeak model was constructed with articulated head, neck, and wing bases for actors to interact with on set. The feathers and skin were fabricated to respond to touch and wind so that eye lines and hand placements would feel authentic.

Flying and complex movement shots replaced the model with computer generated animation based on motion studies of birds and horses. Lighting references from the animatronic were captured on location so the digital creature could match the color and texture of the environment in each scene.

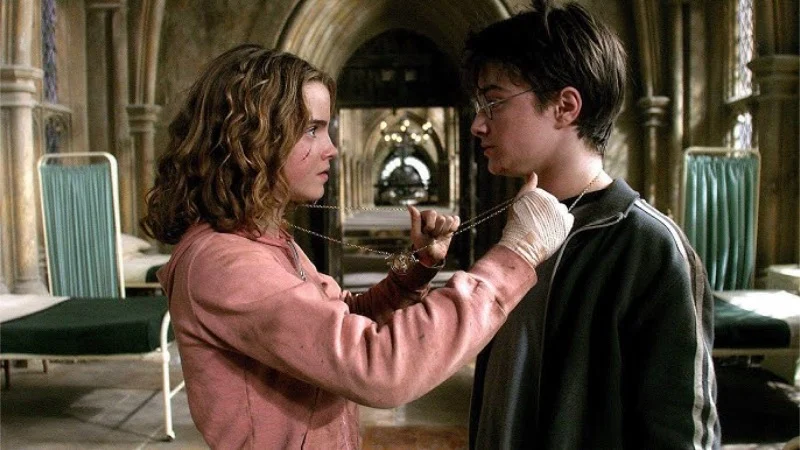

The Time Turner sequence was mapped like a puzzle

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The time travel section was planned with detailed diagrams that tracked character positions and actions across overlapping timelines. Sets were dressed twice to represent before and after states, and camera paths were repeated with motion control so that plates could be layered without drift.

Sound and music were also structured to echo earlier moments so viewers could orient themselves. The team recorded repeated effects and ambient cues in different mixes, then reintroduced them at precise frames to signal where the characters were within the loop.

The shrunken head was created specifically for the film

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The talking shrunken head on the Knight Bus does not appear in the original book. It was conceived during development as a lively element to break up the intensity of the early chase and to give the driver a foil during the wild ride.

Puppetry and partial digital work combined to animate the facial movements in tight shots. The prop department produced multiple versions with different mouth positions so editors could cut between them and maintain sync with the recorded dialogue.

The Marauder’s Map was a functioning physical prop

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The Marauder’s Map used in ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’ was built as a fold out prop with layered sections and delicate line art. The pages included hidden flaps and sliding elements so that camera moves could reveal different parts of the castle in a single take.

Visual effects added the moving footprints and labels, but the base artwork you see is captured from the real object. The team produced backups in various sizes for wide shots and close work, and aged each piece so it would photograph with consistent texture under different lights.

Lupin’s werewolf followed a lean design with elongated limbs

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The look of Remus Lupin’s transformed state stepped away from bulky creature builds and focused on a thinner frame with long limbs and a gaunt profile. This design allowed the character to move quickly through narrow sets and to read clearly in silhouettes during low light scenes.

Makeup tests and digital concepts were iterated to balance recognizability and menace. The final shots used a mix of on set reference performers and computer generated animation, with skin shaders tuned to the cooler palette that defines the night sequences in the film.

Share your favorite behind the scenes detail from this film in the comments and tell us which moment surprised you most.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·