Women suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following sexual assault experience “profound” disruptions of nerve connections in the brain, a new study revealed.

The research presented at the 38th ECNP Congress in Amsterdam uncovers neurological alterations underlying the severe emotions experienced by sexual assault survivors – a group that has historically been underrepresented in neuroscientific studies.

Survivors of sexual assault may experience PTSD, characterised by pervasive symptoms, including intrusive memories, heightened anxiety, emotional numbing, and mood instability.

While PTSD has been studied extensively in the contexts of warfare, natural disasters, and accidents, the neurological effects of sexual assault-induced PTSD have remained elusive, say scientists from the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona in Spain.

Around 70 per cent of women who suffer a sexual assault develop PTSD, according to previous studies.

“Despite sexual violence being one of the most widespread forms of trauma affecting women, most research on PTSD has focused on other types of trauma, such as war,” said lead researcher Lydia Fortea from the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona.

“This is one of the first, and certainly the largest, connectivity study to look at PTSD in sexual assault in teenagers and adult women,” she said.

The new study assessed the brain activity patterns of 40 women with PTSD as a result of sexual assault trauma within the past year, and compared them with a matched control group.

Study participants underwent MRI brain scans to look at nerve connectivity and how they relate to their depressive and PTSD symptoms.

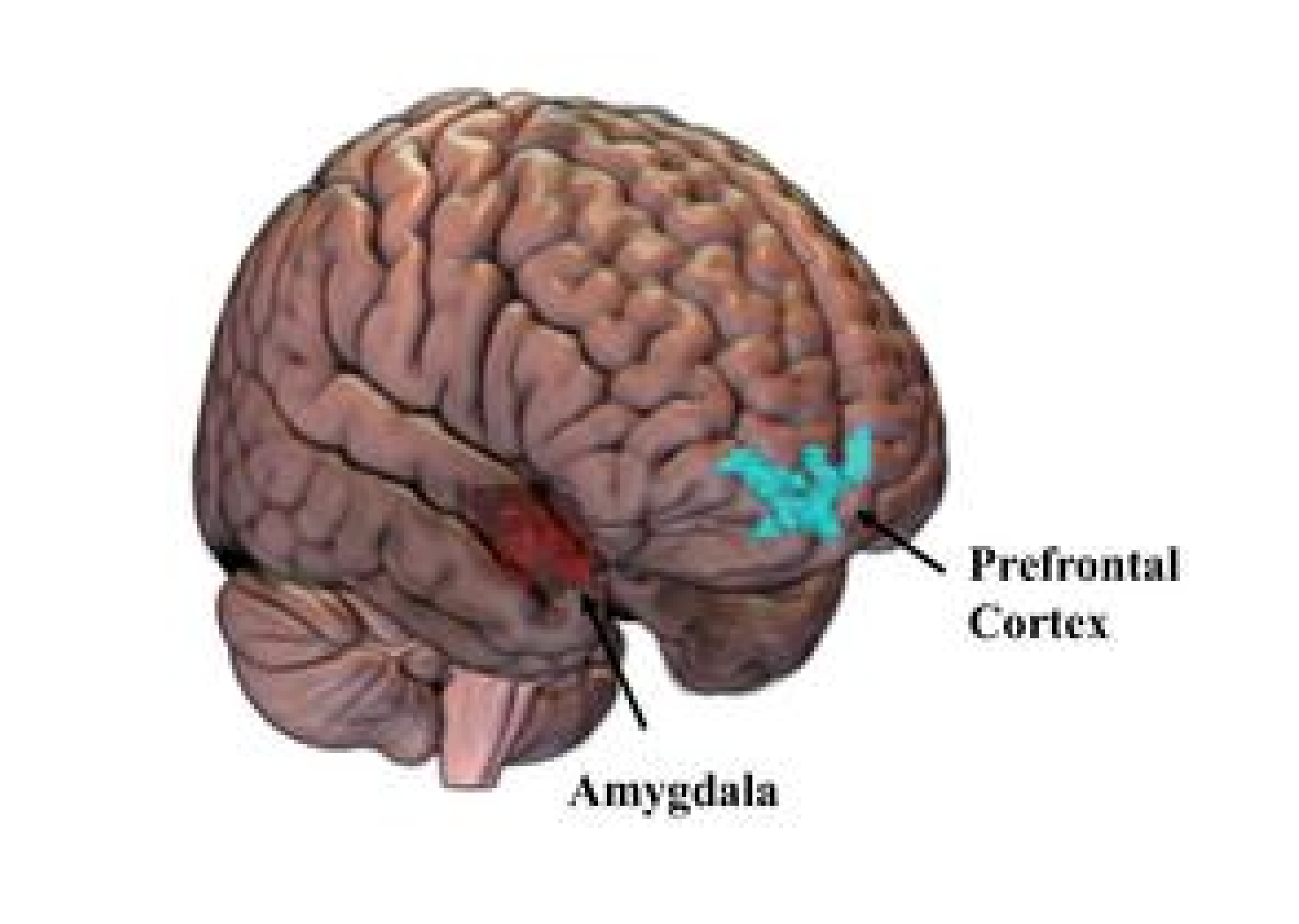

Researchers specifically looked at how key brain regions involved in fear and emotion regulation synchronise with the rest of the brain in women with PTSD following sexual assault.

“PTSD following sexual assault tends to be especially severe and is often accompanied by higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts,” Dr Fortea said.

The latest research reveals that many women who survive sexual trauma show a marked reduction in the usual communication between two important brain areas involved in processing and control of emotions: the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex.

In some women, researchers say the synchronisation between these brain areas can drop to near zero.

“We found that in 22 of the 40 women with PTSD following a recent sexual assault, communication between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex was effectively lost, dropping to zero or near zero,” Dr Fortea said.

“The finding that amygdala–prefrontal communication can drop to near zero underscores the severity of circuit-level disruptions in emotional regulation networks after trauma,” said neuroscientist Marin Jukić from Sweden’s Karolinska Institute, who was not involved in the study.

However, the brain change did not appear directly linked to how severe the PTSD and depressive symptoms of the survivors were.

“This suggests that while this brain difference might be a feature of the disorder itself, it’s not necessarily a sign of how bad the symptoms are; this is probably dependent on other factors,” Dr Fortea explained.

The findings underscore the idea that PTSD after sexual assault is linked to problems in brain circuits that regulate emotion and fear.

“One of the things we will do now is to see if these connectivity disruptions following a sexual assault could help to predict response to PTSD treatment. If so, we would be able to identify early which patients are at risk of worse outcomes and intensify clinical efforts to help them recover,” Dr Fortea said.

Rape Crisis offers support for those affected by rape and sexual abuse. You can call them on 0808 802 9999 in England and Wales, 0808 801 0302 in Scotland, and 0800 0246 991 in Northern Ireland, or visit their website at www.rapecrisis.org.uk. If you are in the US, you can call Rainn on 800-656-HOPE (4673).

.jpeg)

.jpg?trim=0,0,0,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·