Jim Sanborn planned to auction off the solution to Kryptos, the puzzle he sculpted for the intelligence agency’s headquarters. Two fans of the work then discovered the solution.

John Schwartz, a retired Times reporter, has been reporting on the quest to solve the code in the Kryptos sculpture at the C.I.A. headquarters since 1999.

Oct. 16, 2025Updated 6:49 a.m. ET

The sculptor Jim Sanborn opened his email account one day last month expecting the usual messages from people claiming to have solved his famous, decades-old puzzle.

Mr. Sanborn’s best known artwork, Kryptos, sits in a courtyard at the C.I.A. headquarters in Virginia. A sculpture that evokes and incorporates secrets, Kryptos displays four encrypted messages in letters cut through its curving copper sheet. Since the agency dedicated it in 1990, cryptographers both professional and amateur had solved three of the passages, known as K1, K2 and K3.

But the fourth, K4, remained stubbornly uncracked.

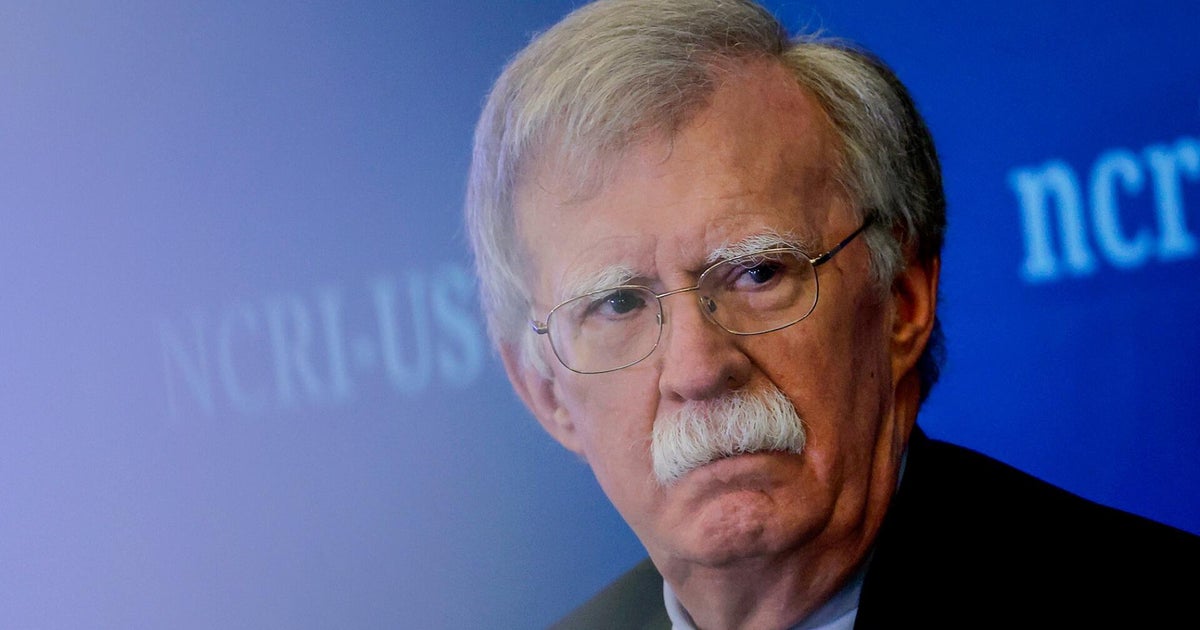

Mr. Sanborn, who is 79, was in the final stages of auctioning off the puzzle’s solution next month. The auction house had estimated that the text of that passage, along with other papers and artifacts related to the sculpture, would bring between $300,000 and $500,000. He has said he intends to use the proceeds to help manage medical expenses for possible health crises, and to fund programs for people with disabilities.

But the email he received on Sept. 3 threatened that plan. Its subject line contained the first words of the final passage of K4. The body of the email showed the rest of the solved text.

Image

What led to that moment is a blend of mishandled paperwork and nerdy spycraft. An amateur cryptographer and his friend had found the solution in plain view for anyone willing to dig through the archives of the Smithsonian Institution.

The hidden text had been uncovered, with potentially damaging effects for the sale — what is the value of a secret that someone else knows?

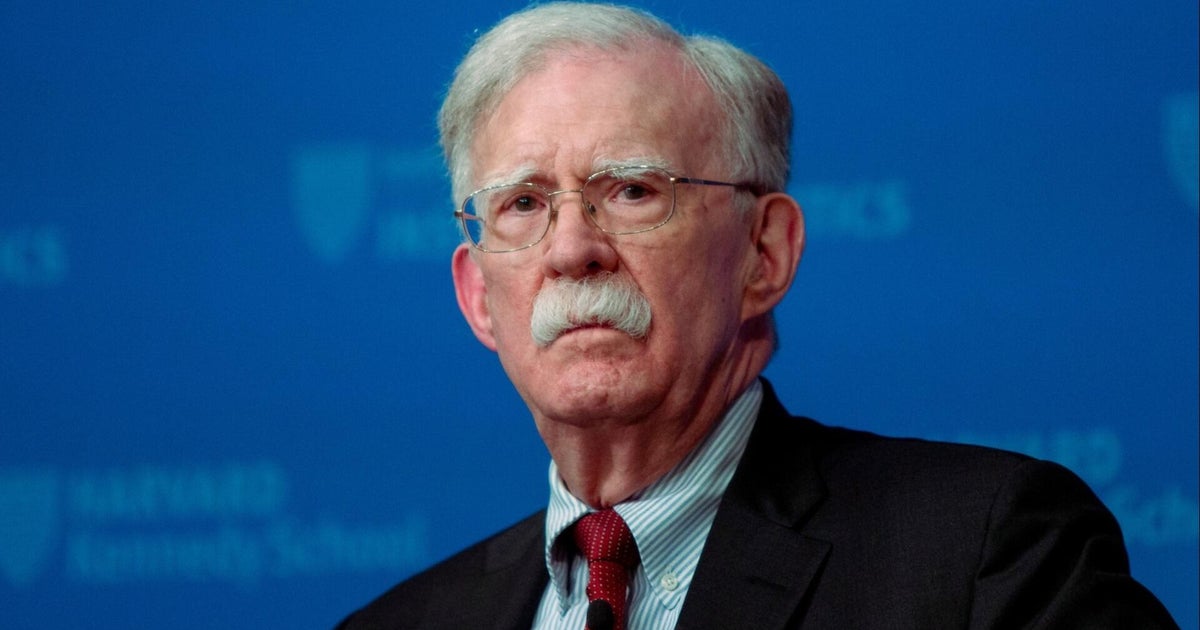

The person who tracked down the solution, Jarett Kobek, is a journalist and novelist long fascinated by Mr. Sanborn’s work. In the announcement from RR Auction, the company running the sale, he saw a reference to copies of the “coding charts” used to encrypt the message; the originals, it said, were at the Smithsonian.

Mr. Kobek lives in California, so he asked a friend in the Washington area, Richard Byrne, a journalist and playwright, to request the Sanborn papers at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Mr. Byrne spent hours photographing documents at the archives on Sept. 2. Mr. Kobek that evening, while reviewing the images his friend sent, saw scraps of paper, some held together by yellowed tape, and got a shock: “Hey — that says ‘BERLIN CLOCK’!”

Those two words were clues to K4 that Mr. Sanborn released in 2010 and 2014. Another scrap had more of what looked like the original, uncoded message, known in cryptography as the plaintext, including the words “EAST NORTHEAST” — two clues released in 2020. Together, there were 97 characters, the number of characters in K4, that he assembled into a readable passage.

“This is a problem everybody has been attacking as a STEM problem,” Mr. Kobek said in an interview, referring to the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics that underlie cryptography. Cryptographic science, he argued, could not solve Kryptos — “but library science could.”

Mr. Byrne compared their find to open-source intelligence.

On Sept. 3, the men sent their email to Mr. Sanborn, including an assurance that their “primary concern” was “moving forward without imperiling your forthcoming auction.” They had a half-hour telephone call in which Mr. Sanborn confirmed that they had the solution.

Mr. Kobek recalled it as “a perfectly lovely conversation.”

But later that evening, a second conversation took a sobering turn, Mr. Kobek recalled. He said Mr. Sanborn proposed they should both sign NDAs and, they could then receive a portion of the auction’s proceeds.

Both Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne said they had to reject the offer, in part out of fear that it would make them “party to fraud” in the auction, Mr. Kobek said.

Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne suggested to him that there should be a way to disclose the fact that the last panel’s solution had been discovered while still holding the auction.

Image

The call ended at an impasse: Mr. Sanborn did not want them to talk, and they were offended by his suggestion that they sign an agreement to stay silent. The offer of money also rankled.

“It’s a complete red line,” Mr. Byrne said. “Nonstarter. Not happening.”

Mr. Sanborn explained in an interview that he created the paper scraps the men had found to share the text with the C.I.A. He had mistakenly included them in the folders he gathered about 10 years ago.

This happened during his treatment for metastatic cancer. “I was not sure how long I would be around and I hastily gathered all of my papers together” for the archives, he said. He was stunned to realize, years later, that the scraps had ended up in the collection.

Mr. Sanborn has since exchanged messages with Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne, but they have not broken through to a solution.

In parallel, on the largest internet forum for Kryptos enthusiasts, the auction catalog had incited a discussion of the Smithsonian trove. On Sept. 5, a member noted that the documents had been sealed and were no longer accessible. That was the work of Mr. Sanborn, who after talking with Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne had gotten the institution to block access to the materials until 2075.

Mr. Sanborn said that his initial reaction to the email, and calls from Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne, was frazzled. “I didn’t know their motives,” he said. He recalled telling them, “If you release that thing, the auction is over.”

Mr. Kobek, long a fan of Mr. Sanborn’s work, said he was devastated by the events of recent weeks.

“If I had known, my God! I never would have sent Rich to this library,” he said.

Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne initially told Mr. Sanborn that they were willing to keep the text private to avoid disrupting the auction. But in interviews, they said the weight of keeping the secret in the superheated world of Kryptos fans is too great, and worried they could be compelled to release the plaintext.

Mr. Sanborn acknowledged that keeping the secret could be a strain: His computer has been hacked repeatedly over the years, he said, and obsessive fans of the work have threatened him. “I sleep with a shotgun,” he said.

If the two men reveal the text, he warned, that “is going to be far worse,” he said. “The world of Kryptos is going to attack” them, he said. “They are going to be pariahs for releasing it.”

The auction house is not sitting idly by.

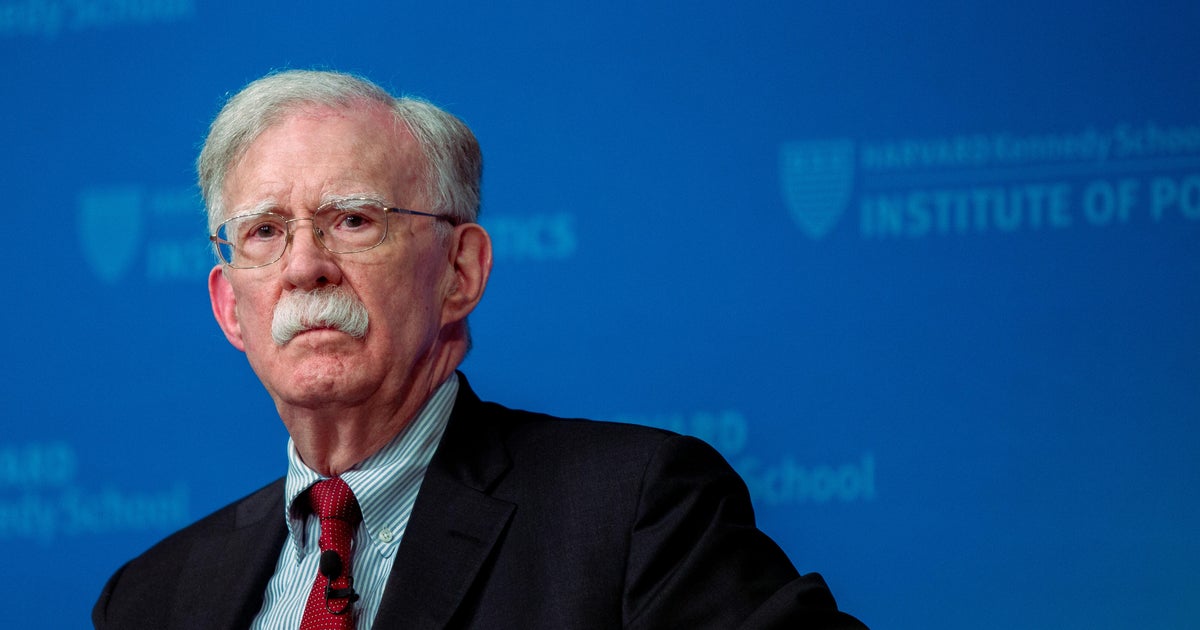

Last week, Mr. Kobek and Mr. Byrne received an email from lawyers for RR Auction that threatened legal action if they published the text, citing copyright infringement and interference with contracts.

In a very different tone, the letter also stated that if the two didn’t publish the text, “you will be looked upon as heroes to the cipher and intelligence communities,” a “story line” their client “would happily help you promote.”

Both men find the legal reasoning dubious and have hired lawyers. But they also acknowledge the crushing cost of defending themselves.

They say they do not plan to release the solution. But they are also not inclined to sign a legally binding document promising not to do so.

Image

Bidding is to begin on Thursday, and close on Nov. 20. The auction house has disclosed the discovery of the solution on their website.

Thomas C. Danziger, a lawyer who represents clients in the art market, said that as long as the message remained a secret, such a disclosure is “the best practice.” And while “presumably, that would have an impact on the value” of the sale, “that still should be cheaper than facing litigation from a disgruntled buyer down the line.”

Mr. Danziger said that revealing the plaintext could have a profound impact on the auction. But while revealing the plaintext could dampen bidders’ enthusiasm, he said, “the auction room is a strange place.”

He cited a famous example: an artwork by Banksy that destroyed itself after being initially sold for $1.4 million at Sotheby’s in London, which “only served to increase its value substantially.”

In the case of Kryptos, “the secret is being shredded before the eyes of the world,” he said. “Does that mean it has less value? Or more value? I don’t know.”

Elonka Dunin, a game designer who helps lead the most active online discussion about Kryptos, said in an interview that she hoped the text didn’t get out. But for true lovers of cryptographic skill, she said, the real challenge is not having the answer but knowing how to get there. “That’s the exciting part for me,” and, she proposed, “the real value” at auction.

“If they don’t have the method,” she said, “it’s not solved,” she said.

11 hours ago

1

11 hours ago

1

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·