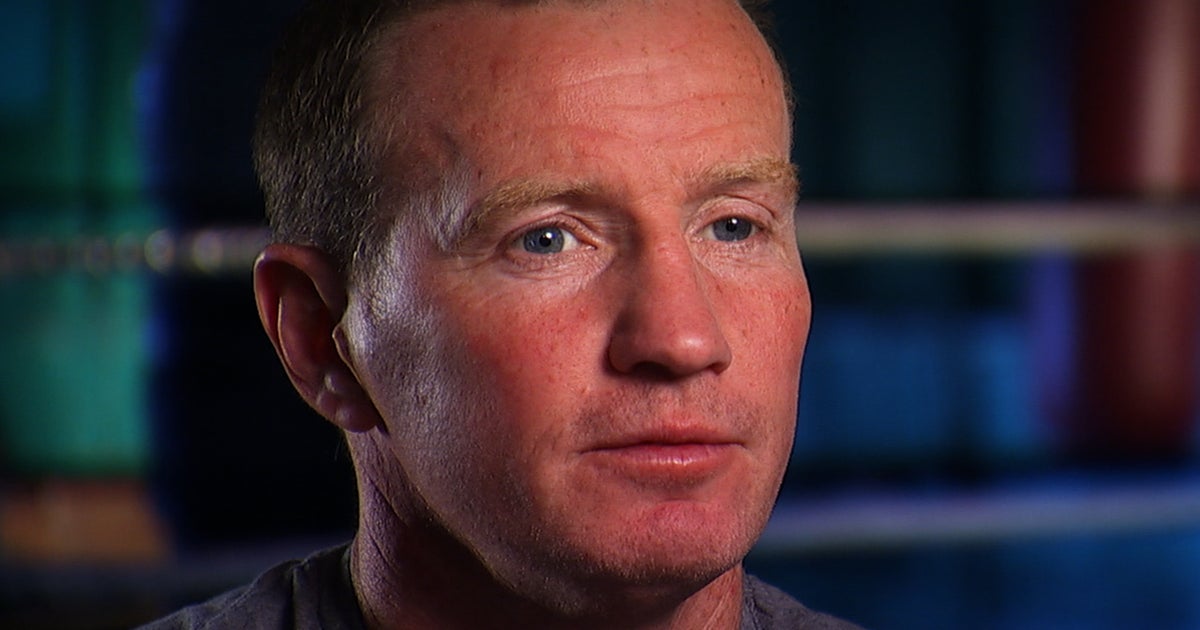

When Mutassim Abdulsatir arrived at Syria's Sednaya prison, accused of so-called state terrorism activities, he stepped into a world of terrifying violence.

"We would lie flat on our bellies like this," he said as he spread his arms over a dirt-floor room.

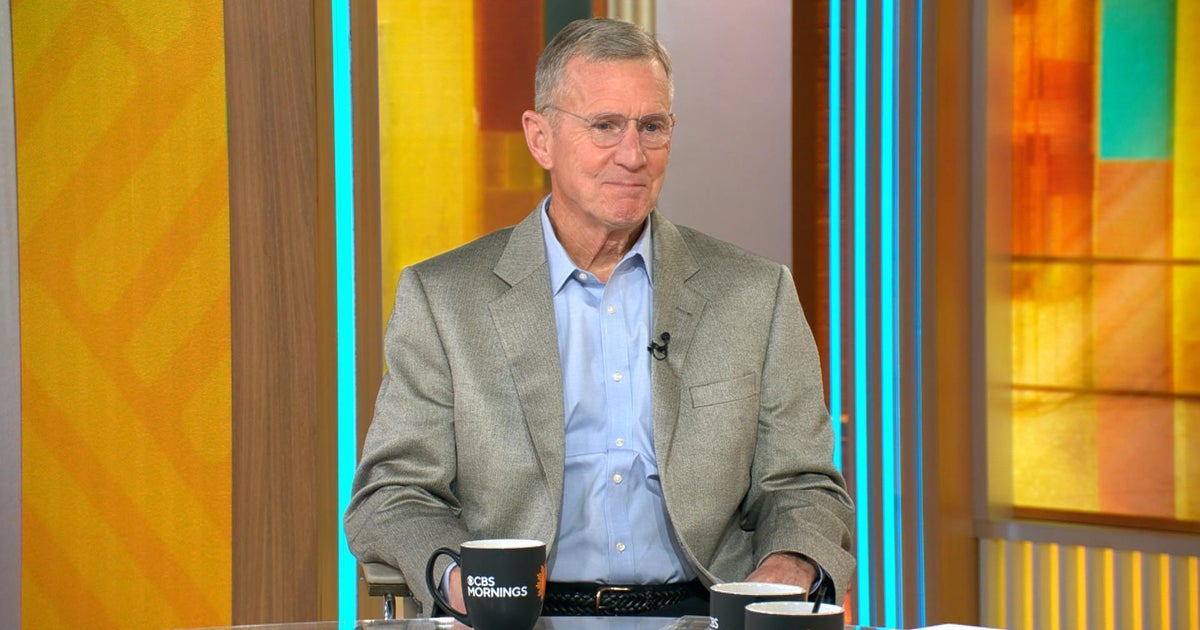

"We'd get hit with pipes over and over again… until some of us died," he told Margaret Brennan, on assignment for a 60 Minutes interview with Syria's new president, Ahmed al-Sharaa.

Abdulsatir was then brought to a dark basement, where he and seven other prisoners huddled in a cell the size of a small bathroom. Abdulsatir said he was locked in there for three months.

He said he watched the guards beat several people to death in his cell. He remembers their names.

"Ahmad Khalid Taree, Samer Abdelrazzak Obaid, Abdulaziz al-Swaid," he told Brennan in the cramped cell.

"Every day, there was a death. It's as if this prison had a policy… as if the guards were required or programmed to kill someone every day."

Brennan told 60 Minutes Overtime that walking through the prison with someone who survived it was an emotional experience for her and the 60 Minutes team.

"He was reliving the entire experience for us in front of our cameras. It was very powerful," she told Overtime.

"Sednaya Prison was a tool of the Assad regime's repression. And we know this not just from prisoners themselves who came out... [but] by human rights groups, by people who really did try to build the case to show the world that there were ongoing human rights abuses being carried out in a really industrialized way by the Assad family," Brennan said.

Human rights organizations have documented execution, torture, beatings, starvation, and deprivation of medicine and medical care within Sednaya's walls.

In 2017, Amnesty International reported on a program of mass execution at the prison during Syria's civil war. They estimated thousands of Sednaya prisoners had been executed by hanging between September 2011 and December 2015.

The report also found that guards had deprived prisoners of food, water, medicine and medical care. Many prisoners watched their cellmates die of starvation, exhaustion, or treatable illness.

"Executions, torture, starvation— it's all deliberate," Brennan told Overtime.

After his harrowing detainment in the basement, Abdulsatir was transferred to a larger cell in what looks like a more traditional prison cell block.

As the 60 Minutes team arrived at the place he called "home," Brennan noticed that Abdulsatir's demeanor changed.

"As hard as it was to come back, sometimes he remembers good things, like the friendships he had," Brennan told Overtime.

"It's like I'm visiting my family… I have some painful memories, but I also have some beautiful memories with my friends," he told Brennan standing outside of his former cell. "I feel that they are still with me."

Abdulsatir told 60 Minutes that speaking was forbidden inside Sednaya's cells. Prisoners could only speak in whispers. If they were caught speaking, they would be beaten.

"One of the things that was or will remain burnt into my memory is him describing what it was like just to be fed," Brennan told Overtime.

"When the guards would bring the food, sometimes they would just take the yogurt, and throw it against the wall, and say, 'Lick it.' That was his protein."

At one point, Abdulsatir said, the pipe that supplied water to the cell was shut off for six days. He said he began to hallucinate, imagining that the water had been turned back on and that he was eating a meal with his family.

"He also described what it was like at night when the guards would come by and say, 'Who's died?'" Brennan told 60 Minutes Overtime.

"They tell us, for example: 'who died next to you?' 'Abdulaziz died next to me.' The guard says, 'Sleep next to Abdulaziz. In the morning, you'll need to write down his number here,'" he explained to Brennan while indicating the number was written on the forehead.

Abdulsatir's description of identifying bodies by writing a sequence of numbers separated by a slash on the forehead sounds identical to a known method of categorizing bodies killed at the hands of Syria's Air Force intelligence branch that was exposed by a former military photographer and whistleblower known as "Caesar."

Suddenly, as arbitrarily as he was detained, Abdulsatir was one day released.

"When they called my name, I [thought I] was going to die. I thought I was going to die or be executed. He told me, 'You're being released! You have received a verdict of not guilty!'"

Abdulsatir showed 60 Minutes a document that he says he was given, declaring him not guilty of state terrorism charges and ordering his release from Sednaya.

"It would've been easier if they had killed me. As much as you're happy to get out and see your family, you cry for your companions with whom you shared memories," he told Brennan.

The Syrian Commission on Missing Persons, established by the transitional government in Syria, estimates that between 120,000 and 300,000 people are still missing.

According to reports by the Association of Detainees and Missing Persons in Seydnayah Prison, where Abdulsatir now works, the bodies of those who were executed at Sednaya were dumped into a mass grave in the nearby Najha cemetery.

Human rights groups believe there are dozens more mass grave sites, and efforts to identify more are under way.

An independent group established by the United Nations called the Independent Institution on Missing Persons in the Syrian Arab Republic hopes to clarify the fate and whereabouts of all missing persons in Syria, and assist in the investigation of mass grave sites.

"What should happen to the people who beat you, who kept you here in this prison?" Brennan asked Abdulsatir, standing outside of his cell.

"We don't want to see them go through what happened to us, because what happened to us would not be acceptable even for animals. We want a fair trial… where a guard would be asked who gave him the orders to kill prisoners by hanging them, or who gave him orders to shut the water off for six days," he told Brennan.

"We would like to know what that chain of command looked like and who was part of it."

Abdulsatir thinks Sednaya prison should be turned into a museum, and a memorial to those who were imprisoned and died here.

"This is the least we could do for the Sednaya prisoners, because they're the ones who led us to freedom."

The video above was produced by Will Croxton. Omar Abdulkader was the associate producer. It was edited by Patrick Lee. The reporting in Syria was done by Margaret Brennan, Andy Court, Annabelle Hanflig, and Omar Abdulkader.

Inside Syria's notorious Sednaya prison

Inside Sednaya prison, the Assad regime's house of horrors

(07:15)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·